December – January 2014 | Statistics

Analysts at World Economic Journal have taken the advice of Goldman Sachs’s Jim O’Neill in replacing Korea with Nigeria in the new grouping of developing economies. They have also evaluated the most important macroeconomic performance indicators of these countries.

The current statistics are relentless: According to 2012 results, the economic growth of the four BRIC countries stalled, and in 2013 the situation did not improve. To judge from forecasts, the opportunities are very limited. This means that investors are beginning to withdraw their assets, from both funds and the countries themselves.

IMF experts are not so pessimistic about the longer term, and they hope that as the world economic situation improves, economic growth will return to these countries. However, what are we to tell investors, who still need to make a return on their investments in the present and not 20 years from now?

After the success of the BRICs, analysts at Goldman Sachs in 2005 chose the “Next Eleven” group of countries that are “destined” for success and dynamic growth in the near future. The ensuing economic crisis has had a noticeable impact on the majority of these countries, but “new stars” have still appeared. By the end of 2012, four countries accounted for almost 75% of the N-11 fund: Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Turkey. Thus, a new acronym was coined: MIST. In November 2013, Goldman Sachs’s Jim O’Neill (who had coined the acronym BRIC), reshuffled the MIST grouping of countries and replaced South Korea with Nigeria, while changing the acronym to MINT. What is hiding behind these four letters, and what can we expect from these countries in the near future?

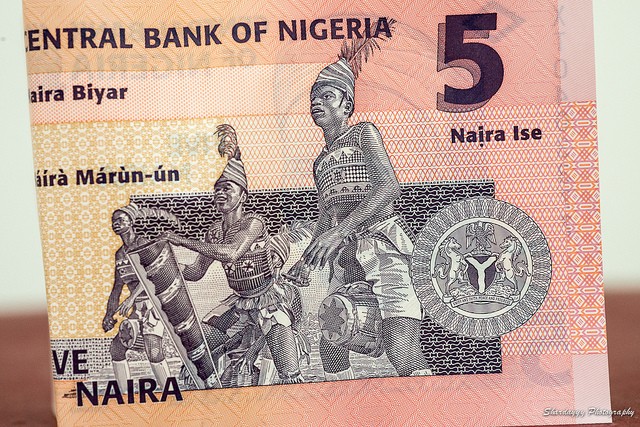

But first we would like to say a few words about the replacement of South Korea with Nigeria. Certainly, Korea would have added more weight to such a group. But in fact this nation can in no way be considered to be a developing country, since its economy has long since grown beyond this framework. In fact, for more than a dozen years it has been considered to be developed, posting better results than many of its peers. Nigeria is a prominent representative of the African continent, occupying a leading place among all its neighbors.

Nonetheless, the MINT countries are very diverse and it is difficult to find anything in common among them. Even when considering the growth of their GDPs, it is difficult to identify any similar trends and patterns. Probably the only thing that they share is a positive outlook for the next two to three years.

Three of the four MINT countries fall within the 11th and 20th largest economies in the world. For example, Indonesia does not hide its desire to improve its ranking even further in the near future. Within the same group Nigeria has a GDP that is 4–5 times smaller than the rest. Nevertheless, both Indonesia and Nigeria had real GDP growth last year of more than 6%, and the rate for 2013 is anticipated to be 5–6%.

On the other hand, the lower the starting position, the more noticeable is growth even if any actual change is insignificant. This, it seems, is O’Neill’s main investment idea. The countries also do not have much in common when it comes to living standards, which can be evaluated in terms of GDP per capita. The countries can be divided into two groups: The indicator is $14,000–15,000 in Mexico and Turkey, which are geographically positioned closer to developed countries, whereas in Indonesia and Nigeria it does not exceed $5,000. In other words, they all have room to grow, especially the last two countries.

Trends in foreign direct investments based on the results of the past year do not make any of the MINT countries look attractive for investment. The inflow of foreign capital fell to 20–30% for three of them. Only Indonesia experienced growth of 3%. Of course, we should state that the level of global FDI in 2012 in general was only 18%. But wtill we can conclude from this indicator that investors do not foresee any long-term projects in any of these three countries. And if there are no projects, then it means there are no real opportunities to stimulate economic growth trends or even to support current levels of growth.

On the other hand, all the countries have increased their foreign debts, but looking at developed countries, this is not the best path of development. Only Nigeria has enough reserve funds to cover its obligations, which is likely due to the low level of its external debt.

Russia and Brazil are often considered to be suppliers of raw materials to China, India, and other nations, and this is considered to be a problem that is preventing them from developing aggressively. But within the new group, two of the four countries also receive significant income from the export of oil, gas and other natural resources. Nigeria is one of the largest exporters of crude oil and gas in the world, with sales accounting for more than 90% of foreign exchange earnings. The country’s prosperity depends on international oil prices.

Mexico is one of the Latin American leaders in its volume of production, and until recently it mainly exported crude oil. But tangible investments in infrastructure have allowed the country to modernize and grow its oil refining base, which can be seen in the increased exports of petroleum products. Mexico’s industrial base does not only consist of drilling operations and oil refineries. In fact, automotive assembly and electronics account for the largest share. The Big Three American automakers – Ford Motors, General Motors, and Chrysler – started opening production facilities in this country back in the 1930s, and European and Asian manufacturers followed suit. These companies also attracted auto parts producers and research facilities to the country. Such diversification adds a number of positives to Mexico’s outlook, and investors are willing to believe in the future of the country.

Indonesia is another country with a developing natural resources sector. But here it’s more a question of future prospects. Production capacity is inadequate, and it requires significant investments, which is limited by the strong presence of the state in this sector, which does not have enough internal financial opportunities itself. Partial privatization would seem to be the best solution.

As for Turkey, its prospects in the near term seem favorable to us, despite the economic performance of the past year. Agriculture, tourism, ship building, and textiles have been the main areas for the export of goods in recent years. Increasing production in these sectors will allow Turkey to further strengthen its position as a leader in the region.

The economic prospects of these countries would certainly be positive, if not for their various political and social problems as well as criminal activity. Reports that Nigerian rebels have blown up a section of pipeline sometimes surface in the news. We also regularly read about drug wars between narcotics cartels and related problems in Mexico. In Indonesia corruption is a huge problem (though it is one that can be found in many emerging markets). And although Turkey is a secular state, religious tensions can flare up suddenly, and the effects of the Arab Spring may even eventually reach here. All this does not negate potential economic successes, but investment risks are noticeably on the rise and it is impossible to ignore them.

If we turn to history and look at the growth of various countries over the last 50–60 years, we can see a clear tendency: Very few countries can sustain growth for more than a decade. In the 1950s it was Venezuela, and in the 1960s it was Pakistan. The success of the latter was replaced by Iraq in the 1970s and Japan in the 1980s. By the beginning of the 21st century the BRIC countries had their turn, but their decade in the spotlight is now coming to an end for various reasons. It is not surprising that new countries have appeared to replace them. The global economy is cyclical. Recession always follows growth and vice versa. It is also predictable that investors begin to seek new “stars” as the income from their current investments shrinks.

Text: Oksana Chaika