BRICS is an informal intergovernmental organization of developing economies aiming to counterbalance the influence of Western-dominated institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The acronym BRICS stands for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, the five initial members forming the geopolitical bloc. It was established in 2009. Since then, more countries, including Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, have joined. Saudi Arabia’s membership is pending confirmation. The bloc seeks to coordinate its members’ economic and diplomatic policies, establish new financial institutions, and decrease reliance on the US dollar. Despite having diverse interests, BRICS members have common values and targets, including but not limited to the following:

• Improving their economic indicators;

• Opposing non-UN-sanctions;

• Pushing for reforms in global institutions, such as changing the UN Security Council and global financial institutions, including the World Bank and IMF.

Below I have prepared a summary of the BRICS members’ key economic indicators. It is based on the European Parliament’s data.

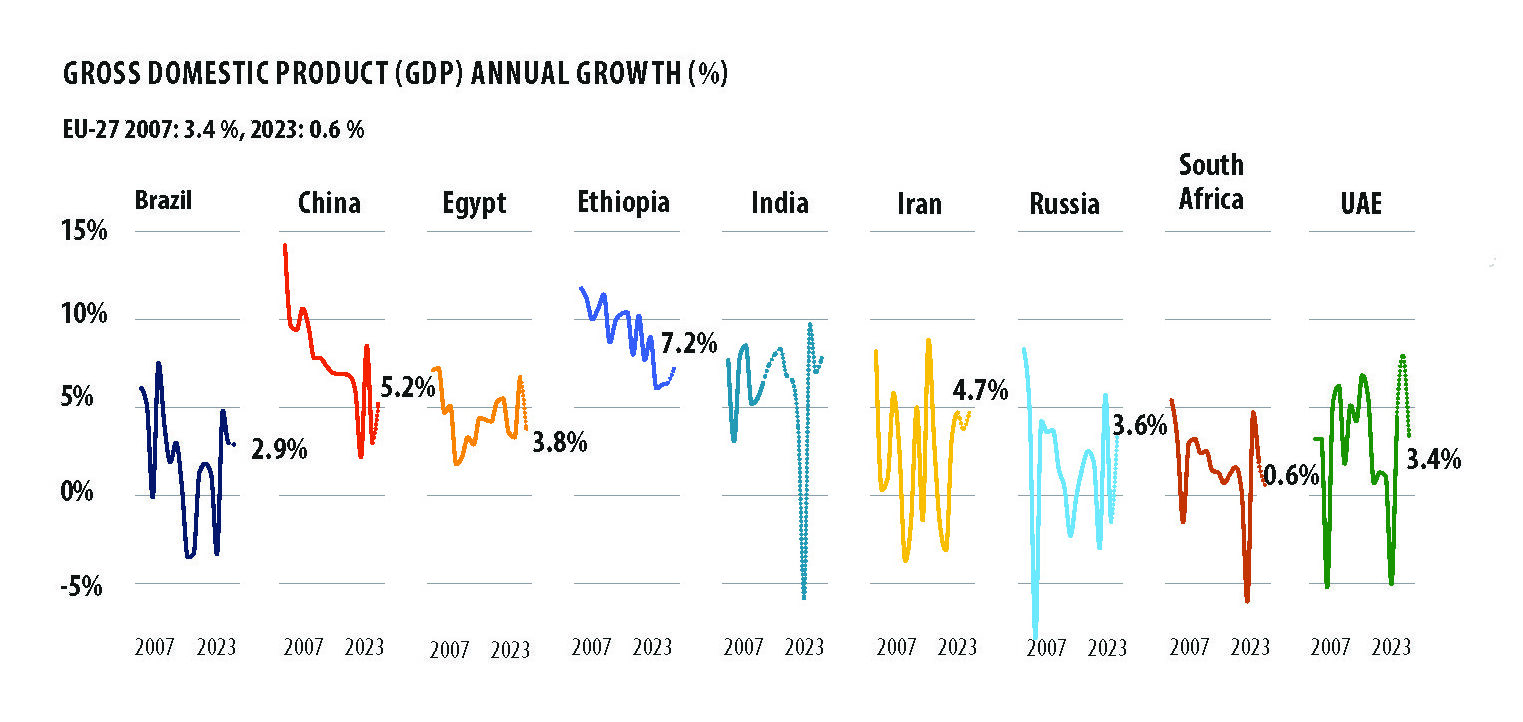

Overall, most BRICS+ countries have higher economic growth rates than developed economies, most notably the EU.

For example, as of 2023, the EU’s growth rate totaled 0.6%. It is so low that we can talk of stagnation. The growth rates of Brazil, China, India, and even Russia and Iran (despite the sanctions) have totaled 2.9%, 5.2%, 7.8%, 3.6%, and 4.7%, respectively.

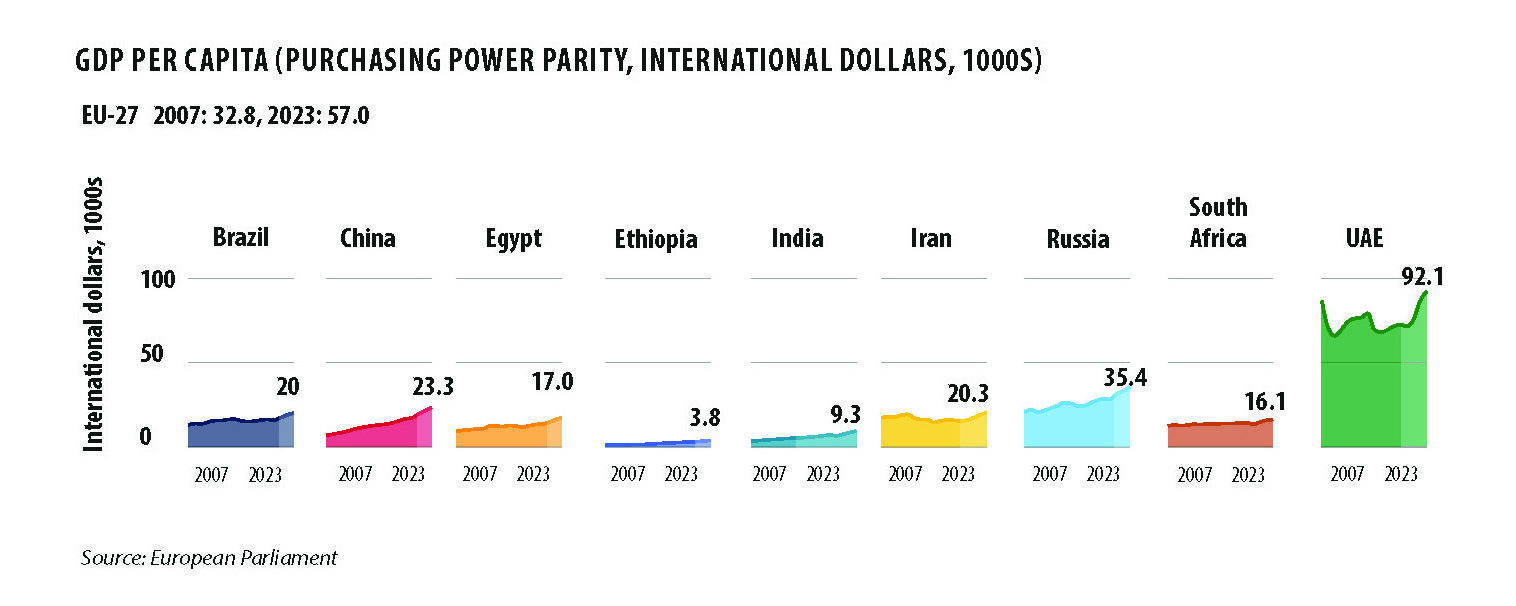

The EU’s GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity, however, as of 2023, was USD 57,000, substantially higher than most BRICS countries, excluding the UAE, suggesting a much higher standard of living in Europe.

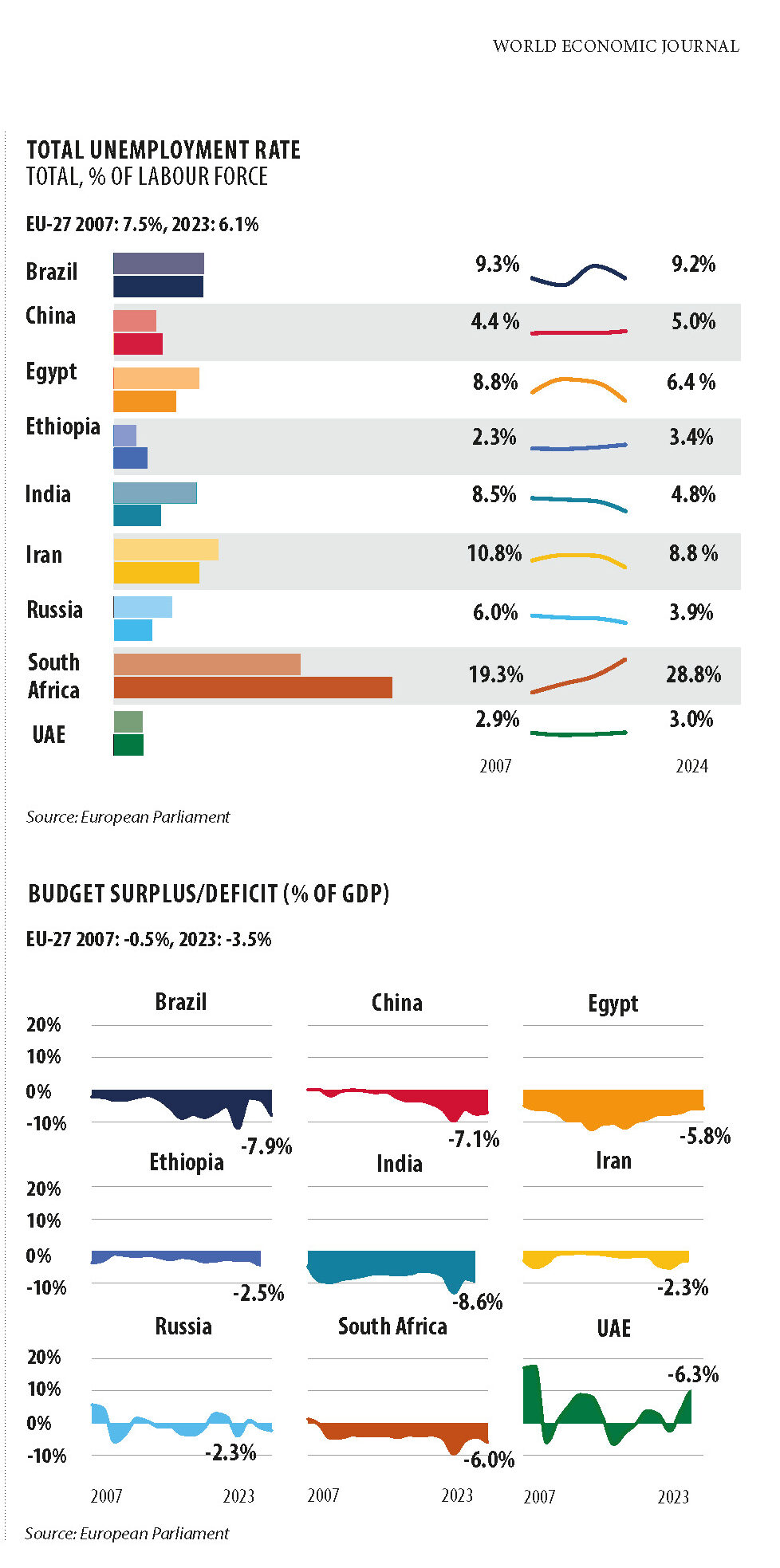

The EU’s unemployment rate of 6.1% as of 2022 is also lower than some BRICS+ countries’. This is especially true of South Africa’s 28.8%, Brazil’s 9.2%, and Iran’s 8.8% unemployment rates.

Most BRICS+ countries have recorded budget deficits just like the EU. However, the EU’s 3.5% budget deficit is even higher than the indicators of Ethiopia, Iran, and Russia.

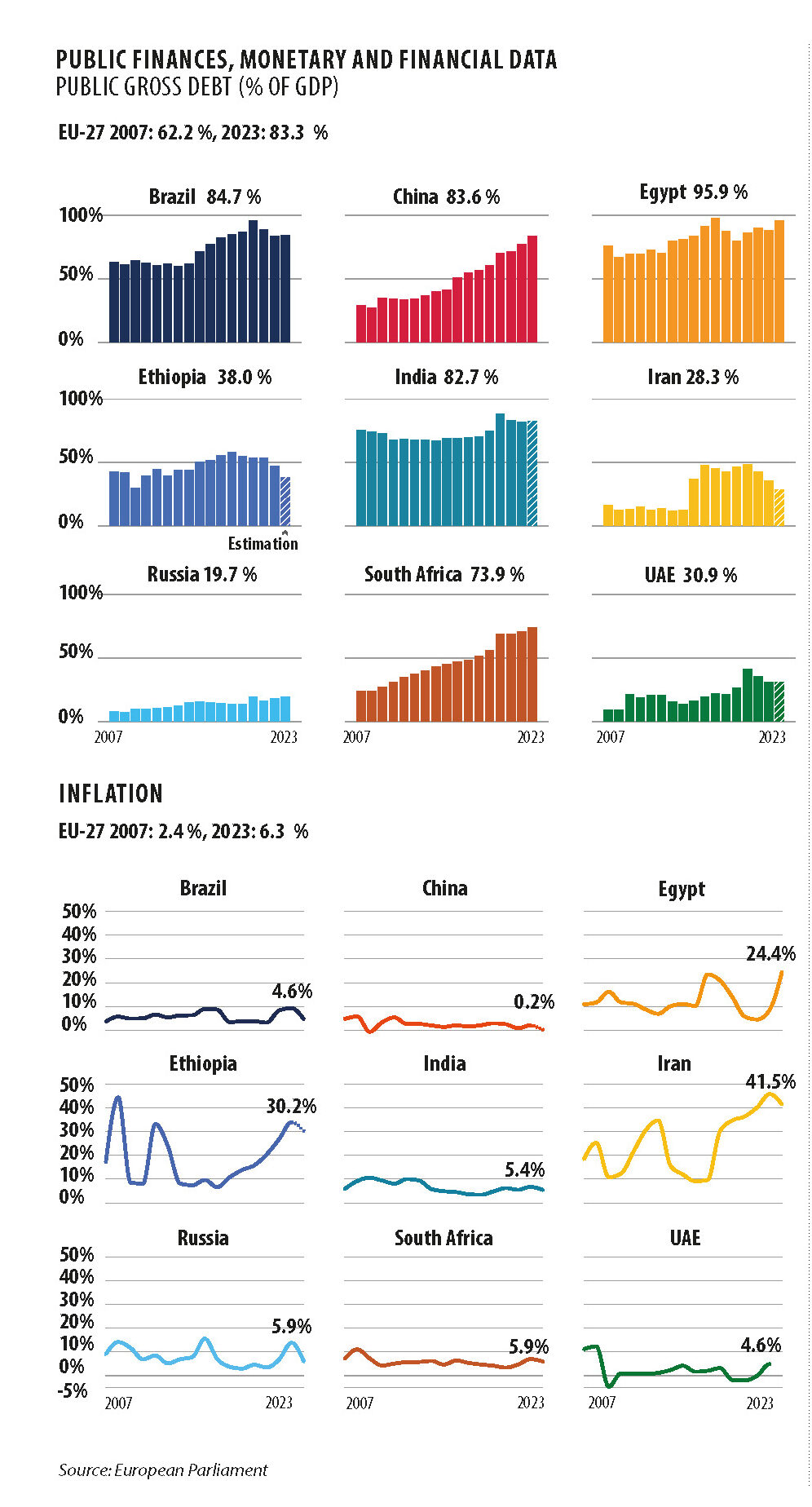

Also quite important is the fact that many BRICS+ countries are less leveraged than the European Union. Russia, the UAE, Iran, Ethiopia, South Africa and even India are less leveraged than the EU. In other words, the EU’s debt-to-GDP indicator is worse than many developing countries’.

Most BRICS countries’ foreign direct investments (FDIs), ownership stakes in foreign companies or projects made by investors, companies, or governments from other countries, are higher than the EU’s. For example, Brazil’s (3.9%), China’s (1.0%), Egypt’s (2.4%%) and Ethiopia’s (2.9%) FDI net inflows as % of GDP, all of these are higher than the EU’s indicator of just 0.9%.

Even some BRICS countries’ inflation indicators are lower than the EU’s 2023 inflation figure of 6.3%. Among these low-inflation countries are China, the UAE, Brazil, India, and South Africa. However, a number of BRICS+ countries with high inflation, including Egypt (24.4%), Ethiopia (30.2%), and Iran (41.5%) have several times higher inflation indicators than the EU. Overall, we can say that compared to BRICS+ members, the EU’s economy is stagnating. In other words, its growth rate is anemic.

ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF BRICS+

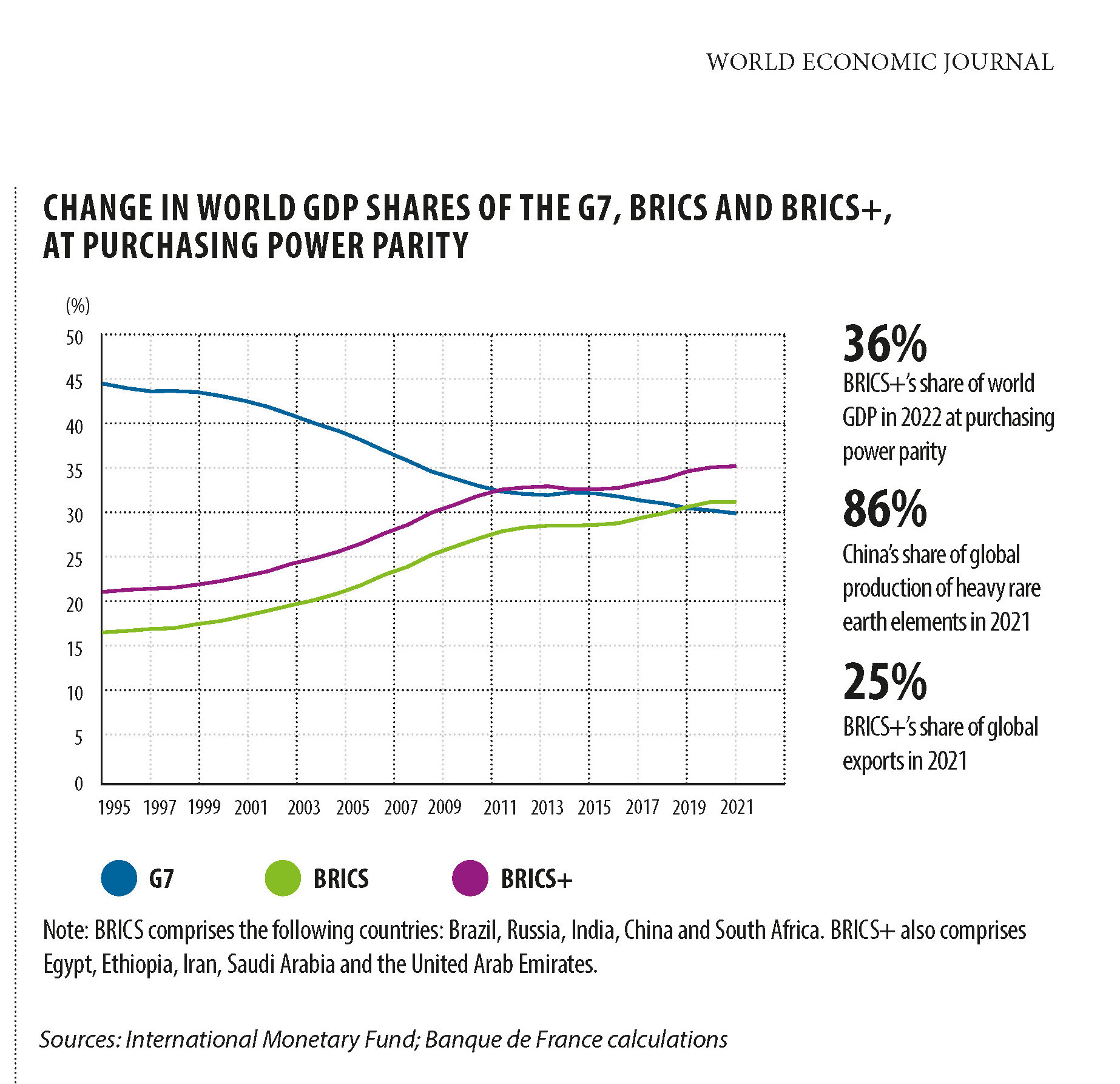

Thanks to the organization’s 2024 expansion, the geopolitical, economic and demographic significance of BRICS+ is growing. The BRICS+ members currently account for 35% of the global economy, based on the purchasing power parity indicator.

As can be seen from the graph on the next page, the G7 share of the world’s GDP has been declining for a few decades. In 1995 the G7 accounted for 45% of the world’s GDP, while in 2022 it was just 30%. BRICS+ countries’ share has substantially increased over the same period.

According to Ahmed Moustafa, director of the Asia Center for Studies and Translation in Egypt, by 2030, the BRICS countries will raise their share in the world’s GDP to more than 50%, thus allowing them to aim for more resources and decision-making power in global intergovernmental organizations. However, concerning the alliance’s desire to influence the World Bank and the IMF, the BRICS+ merely created an alternative, namely the NDB (New Development Bank), in 2014 because, in the group’s opinion, neither the IMF nor the World Bank, Western-led financial institutions, sufficiently reflect its interests.

The rising power of BRICS+ will also likely enable the foundation of new international financial organizations, similar to the NDB and the CRA (The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement), facilitating financing and economic stability for emerging countries. The BRICS founded the NDB in 2014 to facilitate emerging nations’ development. The NDB was established as a competitor and a counterforce to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), of which many BRICS members are skeptical. The establishment of the NDB is considered to be one of the BRICS’ most important achievements. The New Development Bank finances infrastructure development, clean energy, environmental protection, and the construction of cyberinfrastructure in BRICS countries. The financial institution funded a considerable number of projects, including India’s urban rail and Brazil’s wind power complexes. The NDB bank has cumulatively approved loans worth 35 billion USD for a total of more than 100 projects since its establishment.

However, the key way of cooperating between the BRICS+ nations remains trade.

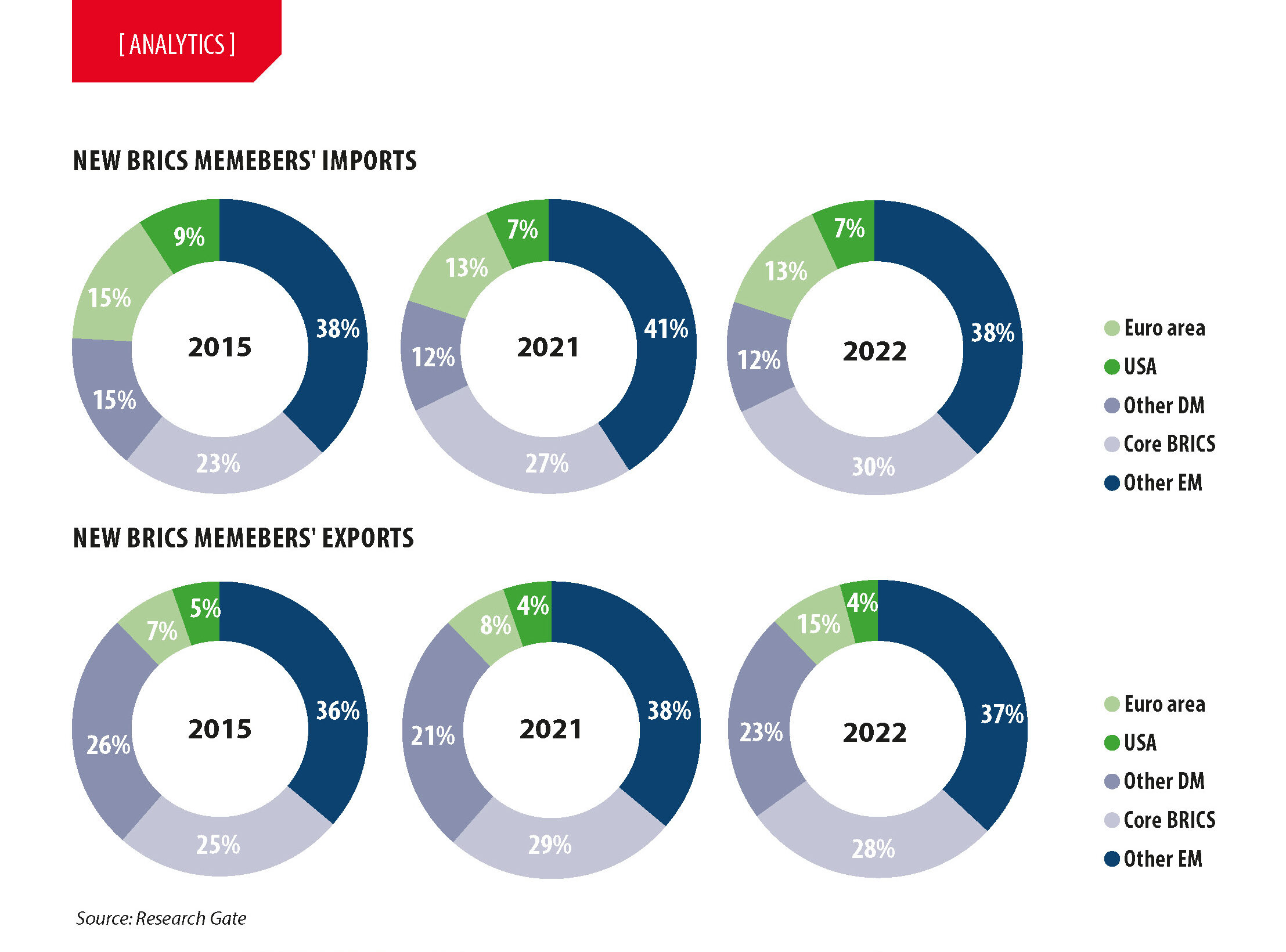

As can be seen from the two diagrams on the next page, which show BRICS+ imports and exports, trade ithin the bloc grew between 2015 and 2022. The trade between the core BRICS members is in blue. Trade with other nations, including the US, the EU, and other developed markets (DM), has become slightly less significant for the BRICS because their shares have somewhat decreased.

According to the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, China’s foreign trade with other BRICS members totaled 4.62 trillion yuan or 648 billion USD, in the first nine months of 2024, a 5.1% year-on-year rise.

This rise can be attributed to the free trade agreements signed between China and other BRICS countries.

Here are the best-performing sectors:

• China’s exports of steel and textile raw materials to other BRICS nations increased by 8.6% and 13.4% year on year in the first nine months of 2024.

• During the same time period, Chinese exports of intermediate products, including integrated circuits, tablet display modules, and airplane parts, to fellow BRICS nations achieved double-digit growth, enabling other BRICS countries to support their emerging industries.

• Trade in agricultural products has also been sound. In the first nine months, more than 80% of poultry and frozen pollack and more than 50% of crabs imported by China were from BRICS countries.

However, trade is not the only way for BRICS+ members to cooperate.

During the 14th BRICS Economic and Foreign Trade Ministers’ Meeting in Moscow in 2024, the participating countries agreed to cooperate in global value chains, digital technologies, special economic zones, green production, electronic documentation, and electronic commerce. The participants also decided to strengthen cooperation in policy exchanges, capacity building, and best practice sharing.

According to Liu Ying, a researcher with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China, BRICS countries can benefit from their absolute advantages by improving economic and trade contacts.

“…the absence of rules, norms, and procedures challenges BRICS in moments like its expansion. How can one analyze and justify the selection of six new members without a formal framework to guide the decision? The choice of some over others can create diplomatic constraints for BRICS, both individually and collectively, in the face of the high interest demonstrated in recent months.”

William Daldegan is a professor at the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), an international relations graduate with a postgraduate program in political science, and the leader of the Research Group on Economics, Politics, and International Development in Brazil.

“There is some risk that expansion will cause BRICS to become incoherent, but New Delhi will find in 2024 and beyond that it has new opportunities to engage with partners such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE and strengthen engagement in the Global South more broadly, particularly with Ethiopia and South Africa.”

Viraj Solanki is a research associate for South and Central Asian Defence, Strategy, and Diplomacy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Moreover, the BRICS can become an important force in fighting trade protectionism. As BRICS members, countries can improve their economic growth rates.

GEOPOLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE AND EXPANSION OF BRICS+

Another question the bloc’s members have to agree on is whether to grow its membership. China and Russia have so far been in favor of expansion. Brazil and India, in contrast, have been more reluctant due to concerns that it would make them less influential members of the organization.

Egypt and Ethiopia’s admission to the bloc will strengthen Africa’s voice in the bloc. Egypt also has close economic ties with China and India, as well as political relations with Russia. Being a BRICS member can help Egypt secure more funding to support its shattered economy.

Due to the fact that Saudi Arabia and the UAE are now the bloc’s members, the alliance now has two significant economies in the Arab world and the Middle East in general. They are also the world’s significant oil importers.

Another source of questions is the bloc’s relations with the G7 countries. Iran and Russia strongly oppose the US dominance. China, in turn, is a strong economic competitor of the US. Also, it is worth noting the US-China tensions around Taiwan. However, Brazil, India, and South Africa have warmer relations with the US. Moreover, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been the US’s close allies in the Middle East.

But how has the collective West reacted to the BRICS’ expansion? In short, Western countries have not taken the bloc’s growth seriously. For example, White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said that the US does not consider BRICS a geopolitical adversary. The only US official to have publicly reacted negatively to the BRICS expansion was Donald Trump. I will explain the reaction of the newly elected president later in this analysis. Likewise, Annalena Baerbock, the German Foreign Minister, says Germany has no reason to worry about BRICS’ expansion. According to many political experts, the bloc’s ambitions are exaggerated because the members have numerous domestic problems and cannot be a real threat to the West.

In the meantime, it is worth pointing out that the USD can quickly lose its status as the world’s reserve currency and as a medium of exchange in global trade. The brilliant position of the USD is due to the Treaty of Bretton Woods. This agreement, signed during World War II, proclaimed the dollar the world’s reserve currency. That is why the demand for the USD has remained very high from foreign countries and has therefore allowed the US Federal Reserve to print more dollars to finance the mounting US national debt while keeping inflation levels at a reasonable level. That is why ignoring BRICS as a major economic and political force “is no longer an option,” said Tufts University scholars in 2023.

ADVANTAGES AND RISKS OF BRICS+ EXPANSION

So, what are the main advantages and disadvantages of the BRICS+ expansion, and how can the growing bloc affect the world order?

In short, BRICS+ could make a substantial global impact in the following five areas.

1. First, it is energy because BRICS+ unites some of the world’s biggest energy exporters and importers. Thanks to the fact that Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are the bloc’s new members, 32% of world output of natural gas and 43% of crude are due to oil BRICS+ member states. These numbers will only rise if Kazakhstan, Kuwait, and Bahrain get admitted to the alliance. 38% of the world’s petroleum imports are also dueto BRICS+ countries. The top petroleum imports are from China and India. If all new potential entrants eventually become members of the group, that number would increase to 55%. Many energy buyers and sellers who are members of the same bloc could even create a parallel energy trading system. That would allow BRICS+ economies to reduce their exposure to the Western-led monetary systems and institutions, thus becoming less sensitive to future potential sanctions and other forms of political and economic pressure. These countries would, therefore, be able to even influence oil prices.

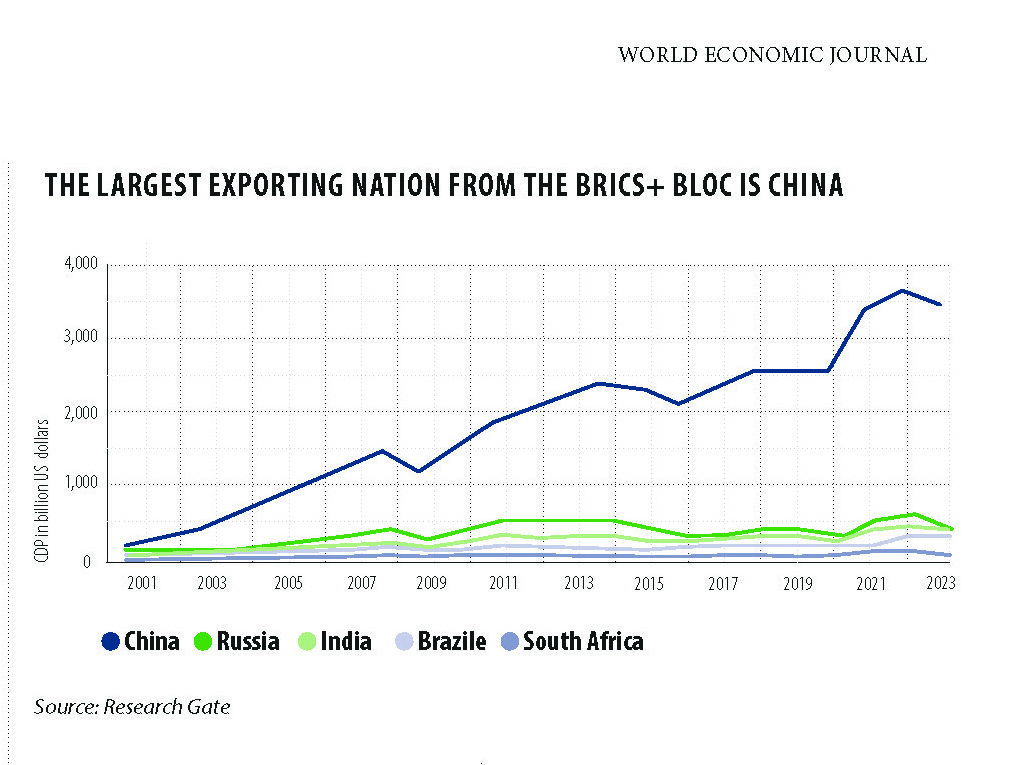

2. Trade opportunities also remain the key to BRICS+. Trade has been a major economic growth stimulus of BRICS+. The share of global trade in goods transacted among the bloc’s current members more than doubled to a total of 40% from 2002 through 2022. China’s rising role as a supplier of industrial and consumer products and a commodities importer has been one of the bloc’s key players. China has become an important buyer of Brazilian soybeans and iron ore and an essential seller of sophisticated products, including electric vehicles (EVs), solar panels, and industrial machinery.

32% of world output of natural gas and 43% of crude are due to oil BRICS+ member states. 38% of the world’s petroleum imports are also due to BRICS+ countries

3. Although several BRICS+ countries, including the Gulf Cooperation Council, have free trade agreements within the organization, no free trade agreement includes every single BRICS+ country. Now, with the organization’s expansion, this problem is solved. That is why BRICS+ could help its members benefit from greater trade opportunities.

4. Infrastructure and development financing. One of the most important BRICS projects in this area has been the New Development Bank (NDB), which was capitalized at $100 billion. This bank finances China’s Belt & Road initiative. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, India, and Russia are stockholders in the China-led Asian Infrastructure & Investment Bank (AIIB) and have received debt financing from it. By 2023, the NBD and AIIB together had invested $71 billion in credit across numerous projects, including but not limited to public health, infrastructure, and clean energy. Obviously, BRICS+ companies benefit from such investments. The admission of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other cash-rich countries could additionally increase the BRICS+ financial resources.

5. Now, we are coming to another vital way to cooperate, namely the BRICS’ monetary policies. As I have mentioned before, BRICS+ countries aim to develop more independence from the international monetary system controlled by the collective West. About 90% of the world’s foreign exchange transactions are conducted in USD through American and EU financial institutions. Western financial sanctions on Russia, especially the freezing of the Russian government’s, Russian companies’, and Russian citizens’ assets in European and US banks highlighted the need to move away from Western-based monetary systems. Thanks to the fact the BRICS+ group includes leading commodity buyers and sellers, the bloc can show the world how countries can move away from the USD.

So, both the bloc’s national currencies and the creation of a common currency are possible. The NDB, for example, has issued about 20% of its loans in Chinese yuan. The bloc has even launched a payment app—BRICS Pay—that allows buying and selling in a few non-USD currencies. Apart from being an effective way to ease the effects of sanctions, this can also save the member countries from foreign exchange volatility during economic recessions. The Payment Task Force, the Think Tank Network for Finance, and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement were established by the BRICS to be used instead of IMF funds to help countries deal with financial crises.

6. New technologies are another way for BRICS countries to cooperate. For example, the BRICS+ Space Cooperation Joint Committee, based on partnerships between Russia and China and China and Brazil, a Partnership on the New Industrial Revolution, and a Center for Industrial Competencies were established by BRICS. These projects promote cooperation and innovation in areas such as intelligent manufacturing, AI, digitalization, and green energy. Developing countries can, therefore, get better access to new technologies, create more intellectual property, and become more technologically advanced in general.

It is likely that BRICS+ will develop more formal institutions and agreements in the coming years. BRICS+ economies are likely to experience substantial growth over the following years. Despite the group’s lack of official trade and investment agreements, it already has high trade volumes between its members.

BRICS+ will likely further invest in infrastructure, thus improving the business environment and technological progress. Transportation, digital communications, energy, and other projects will lead to higher demand for international companies’ products and services, thus providing opportunities for investors and creating more jobs. The New Development Bank, for example, is financing 15 transportation infrastructure projects in the Indian

subcontinent.

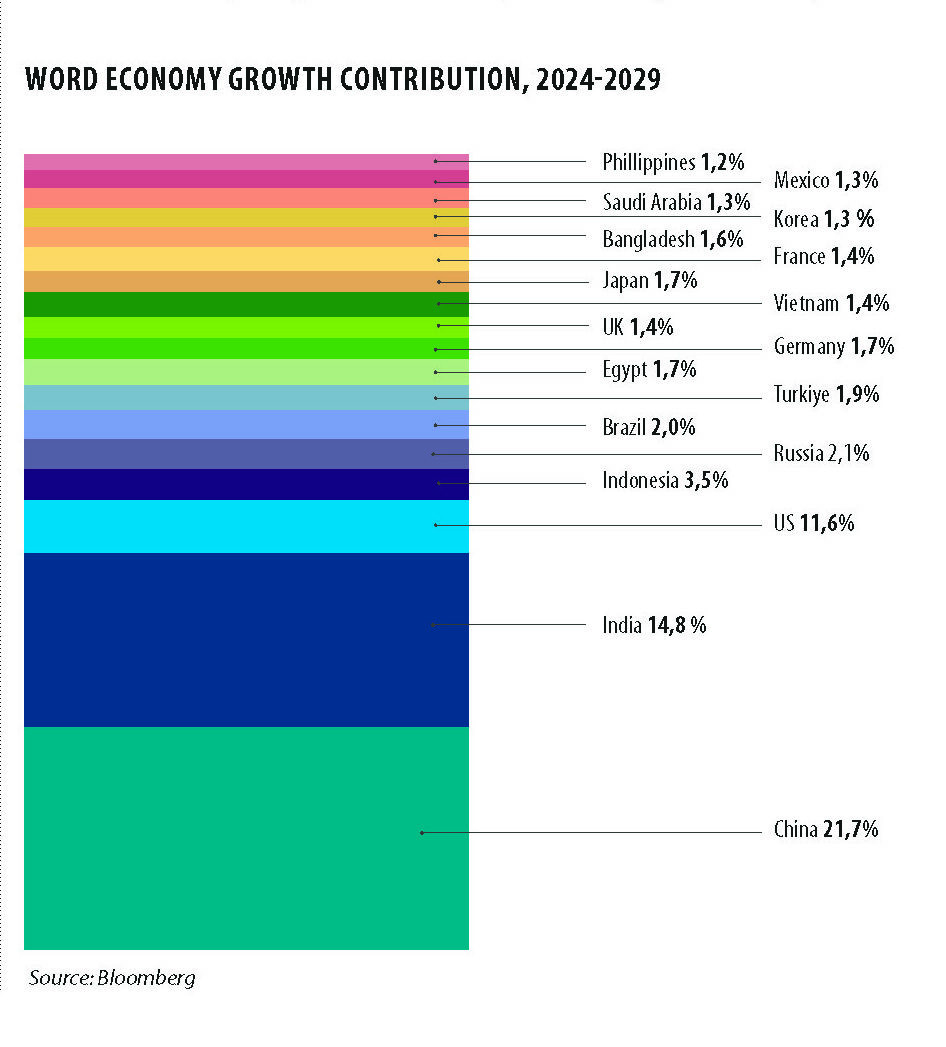

THE FUTURE OF BRICS+

According to the International Monetary Fund’s recent report, medium-term growth for the global economy is expected to remain low. According to the IMF’s projections, the forecast for global growth is 3.1% in 2029—one of the lowest five-year-ahead projections in decades. According to the IMF’s and Bloomberg’s forecasts, a large proportion of growth over the next five years will come from BRICS economies, including China, India, Russia, and Brazil. By contrast, the expected contribution of G7 countries, including the US, Germany, and Japan, was revised. According to Bloomberg’s estimates, it is widely expected that China will be the top contributor to global growth over the next five years, with its 22% share bigger than all G-7 members combined. India is the second-highest-growth country.

“An analysis of BRICS’ founding and new members highlights their divergent interests. China and Russia strongly oppose the U.S.-led global order but lack a cohesive set of values behind this stance, while India pursues a multi-alignment strategy, engaging with both the U.S. and the other major powers. Brazil and South Africa, though less confrontational, have also adopted flexible foreign policies, engaging actively in global affairs, particularly in regions like the Middle East… These disparities among BRICS members reveal a group more defined by its differences than by any shared values or interests. Rather than a unified bloc, BRICS stands out for its diverse internal challenges and the complexities they bring.”

Burak Elmalı is a researcher at the TRT World Research Centre in Istanbul. He holds an MA in Political Science and International Relations from Boğaziçi University.

It is expected to add almost 15% of the total through 2029. The diagram on the previous page illustrates this.

The bloc’s 2024 priorities include integrating new member countries and establishing a new category of BRICS nations that will not receive full membership but will cooperate with the bloc. BRICS is seeking to grow further, as I have mentioned in the previous sections. Current members aim to attract more members and partner nations to have access to other trade organizations.

The countries invited to join the bloc as “partner states” include Türkiye, Indonesia, Algeria, Belarus, Cuba, Bolivia, Malaysia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Thailand, Vietnam, Nigeria, and Uganda. These partner states might eventually become full members.

Obviously, this expansion comes at a cost. Some US officials see a threat to America’s global dominance from the bloc.

Recently, the newly elected president, Donald Trump, said he would demand that BRICS countries cancel their plans to create a new common currency. If they do not agree, they will face 100% tariffs during his presidential term.

According to Mr. Trump, the BRICS members are trying to cease using the USD. Obviously, this is a threat to the USD, which is the world’s reserve currency. According to Donald Trump’s post on Truth Social, the US government should “require a commitment from these countries that they will neither create a new BRICS currency nor back any other currency to replace the mighty U.S. dollar, or they will face 100% tariffs, and should expect to say goodbye to selling into the wonderful U.S. economy.”

These statements come for a reason. In 2023, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, suggested creating a common currency in South America to stop relying on the USD.

Either creating a common currency, trading in BRICS national currencies, or using banking networks outside the USD-denominated system could allow member countries, including Russia and Iran, to bypass Western sanctions.

But what are the chances of a new currency? After all, the alliance has economic and geopolitical differences. However, most of its members do not want to rely on pro-Western institutions and be affected by sanctions.

During the BRICS countries’ summit that took place in Russia in October 2024, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the bloc was “not considering this issue” simply because “its time has not come yet” and “we need to be very careful and act gradually, without any rush.” At the same time, Mr. Putin said the bloc was looking at “the possibilities to make wider use of national currencies” and facilitating coordination between member states’ national central banks to enable trade.

The BRICS+ expansion would probably attract increasing attention from Western countries, including the US, due to the BRICS’ rising economic potential, the group’s expansion, the emergence of international intergovernmental organizations, like the New Development Bank, and the broader move from the USD.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

SOURCES:

European Parliament – www.europarl.europa.eu

Business today desk – www.businesstoday.in

Central Bank of France – www.banque-france.fr

Global Times – www.globaltimes.cn

Investing Strategy – investingstrategy.co.uk/

Research Gate – www.researchgate.net

The State Council – english.www.gov.cn

Belt and Road Portal – eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn

Africa News – www.africanews.com

The Economist – www.economist.com

AA – www.aa.com.tr

Geopolitical Monitor – www.geopoliticalmonitor.com

Asia Nikkei – asia.nikkei.com

Council of Councils – www.cfr.org

Corporate Finance Institute – corporatefinanceinstitute.com

Tufts University – fletcher.tufts.edu

Boston Consulting Group – fletcher.tufts.edu

E-International Relations – www.e-ir.info

The International Monetary Fund – www.imf.org

The Washington Post – www.washingtonpost.com

BNN Bloomberg – www.bnnbloomberg.ca

Brasil de Fato – www.brasildefato.com.br

CNN – www.cnn.com

By Anna Sokolidou

PHOTO: PELOTAS MUN; PHOTO: IISS; PHOTO: TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE.

Stay informed anytime! Download the World Economic Journal app on the App Store, Google Play, ZINIO, Magzter and Issuu:

https://apps.apple.com/kg/app/world-economic-journal-mag/id6702013422

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.magzter.worldeconomicjournal

https://www.magzter.com/publishers/World-Economic-Journal

Issue FEBRUARY – MARCH 2025 – World Economic Journal https://www.zinio.com/publications/world-economic-journal/44375