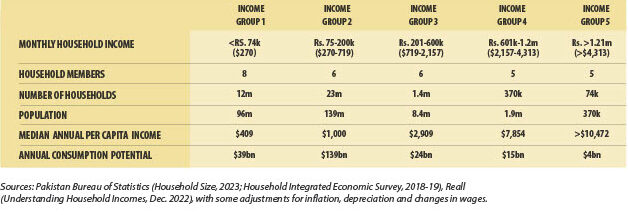

It is the first thing on everyone’s Pakistan presentation—its 250-million population. Who wouldn’t be impressed by such a large number of potential customers? While size does matter, this number alone does not tell the whole story. To identify the correct business models and strategies to pursue, it is important to understand the breakdown of the 37 million households and incomes within that population.

GROUP 1 – Nearly one third (32%) of households is below the poverty line with a household income under Rs. 75,000 per month. These households are extremely price-sensitive and time-insensitive. The journey towards truly having any monetisable use-case for this group will require decades 72 of structural changes for them to be included as a large enough market to serve. This is the labour class of Pakistan, who can be lifted out of poverty only when a social safety net will be created. The upper-quartile of this class are expected to join the lower quartile of the new emerging lower middle class, as discussed below, in the next decade. Migration to Gulf countries and other more developed markets is a trend worth observing, as it could accelerate the transition of this group into the lower middle class more quickly than anticipated.

GROUP 2 – The better part (62%) of Pakistani households generate an income between Rs. 75,000 to 200,000 per month. These households are very price-sensitive and partially time-sensitive. This is the silent majority or the bulk of where people fall in the country, with the likes of Daraz and Bykea targeting households in the upper quartile of this range. This market is expected to experience the greatest level of upward mobility over the next 10 years, with average income per capita rising at least 25% and up to 40%. This is the long-tail of the Pakistani consumer market.

GROUP 3 – A small fraction (3.8%) of households generate an income between Rs. 200,000 to Rs. 600,000 per month. These households range from price-sensitive to very price-sensitive and partially time-sensitive to very time-sensitive. This can also be called the upper middle class of Pakistan, which has part-time drivers and maids, but focuses their spending on education, investments and travel. They are also discount-driven and careful with their spending, yet typically have at least two working members in the household, which necessitates a high level of convenience. This group often shops at more upscale grocery stores and prefers branded products. They tend to be more private but also aspirational, frequently timing their online purchases to coincide with sales, though they rarely participate in group buying. This is the core market for Bykea, Daraz, FoodPanda and formerly Airlift. A medium-term opportunity with this group lies in engaging the Gen Z segment, which is more social and drawn to gamification and non-monetary incentives.

A summary of consumption by household segments in Pakistan

GROUP 4 – Accounting for just 1%, wealthy households generate an income between Rs. 600,000 to Rs. 1,200,000 per month. These households range from partially price-sensitive to price-sensitive and time-sensitive to very time-sensitive. However, these households typically employ drivers, maids, and other helpers for most tasks and chores, so they rarely use activity outsourcing models. They prefer in-store shopping for a more personalised experience, although the younger, more digitally savvy members increasingly favour online shopping. This group represents the most immediately monetisable user base in Pakistan, but highly brand-sensitive and individualistic, with their spending focused on quick commerce, direct-to-consumer brands, fast fashion, and branded electronics. Most discount-driven marketing efforts target this segment, which is ideal for banks, quick commerce, premium brands and boutiques. With about half of this population in their early 50s and above, attracting the younger generation is crucial for longterm economic gains. This is because purchase decisions are usually initiated by the younger members, making the older ones more of financiers than purchasers.

GROUP 5 – The ultra-wealthy population (0.2% of households) generate an income above Rs. 1,200,000 per month. T hey are neither price- nor time-sensitive and live a very sheltered lifestyle compared to the rest of the population. T hese households are the iPhone and X/Twitter users of Pakistan but are demographically skewed to be much older, with fewer young people, and a focus on premium online stores, which in effect means buying imported products such as M&S olive oil and Huda Beauty foundation at eye-gouging premiums. Extremely brand conscious and private by necessity, they rarely shop in the country and mostly seek lifestyle/ultra-luxury brands.

For many business models, particularly those prevalent in more developed markets, the true addressable market might be only around 10.6 million people

Where does that leave the magical 250 million population figure in reality? For many business models, particularly those prevalent in more developed markets, the true addressable market might be only around 10.6 million people (including all of Groups 3, 4, and 5). This is still a $43 billion opportunity, or maybe just half if factoring in the propensity and ability of different ages within those groups to adopt technology.

MARKET REALITIES FOR B2C BRANDS

When looking at consumer segments in Pakistan from a socio-economic angle, measuring both household consumption potential and per capita income, it is clear that consumption differs drastically from income segment to income segment.

For the last two years, the cost of living has increased dramatically for the overwhelming majority of households in Pakistan. With much less discretionary income available, consumers are not in the position to pay large premiums.

This has led a significant number of quality-oriented consumers to change their buying criteria to one of highest perceived value and for value-oriented consumers to double down on their discount hunting habits.

This is evident in the grocery market, which is estimated to be worth at least $50 billion. Most Pakistani households allocate at least 25% of their income to groceries, with Income Group 1 spending up to 50%. This leaves minimal room for discretionary spending, especially when considering the need for emergency healthcare funds and ongoing children’s education expenses.

When it comes to distribution, most brands today use the Internet more than ever in Pakistan, with more than 50 million social media users. However, numerous brands lack the expertise or team to effectively optimise their cost-per-acquisition through online channels, resulting in suboptimal returns on ad spend.

In Pakistan, identifying your customer and delivering your message are distinct tasks, with reaching the right customer often being a monumental challenge. This difficulty is closely tied to the diverse socio-economic consumption potential across Pakistan’s various income groups. Only brands that can successfully navigate the complexities of these income group changes are likely to become national-level brands.

MATCHING SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALITIES

The experiences of successful consumer brands in Pakistan underscore essential requirements for companies aiming to establish a digital-first business in the country. Brand strategies must align with Pakistan’s socio-economic realities for years, if not decades ahead. Here are fundamental rules to achieve this.

- Targeting the right customer is more important than continuously improving the product. Take Income Group 1, for example: it not only lacks consistent discretionary purchasing power despite its substantial collective consumption but is also less likely to engage based on product quality or to become repeat customers. Higher margin discretionary products should rather focus on higher LTV users with a focus on nationally scalable marketing strategies that resonate across income groups.

- Value is measurable and apparent to customers—deliver it to convert and retain them. A successful model to cater to the majority of users in Pakistan requires a value-first approach that delivers immediate savings. A strategy that highlights your pricing advantage along with your ability to offer superior convenience provides an immediate and obvious value add, fostering natural virality. When examining Income Groups 2 and 3, there is sufficient collective spending power and improved per capita income, allowing for a broader variety of SKUs to be consumed. While price sensitivity remains high, these groups exhibit greater trust in technology. This is significant because high trust in technology correlates with higher education levels, income, and digital adoption—factors strongly associated with clear and rapid upward mobility in income level1.

- Purchase frequency is king for mass affluent consumer targeting brands. The top half of Group 3, along with Groups 4 and 5, constitutes the immediately addressable mass-affluent user base. These consumers are drawn to premiumisation, value productivity hacks, and exhibit a blend of individualistic and collectivist buying behaviours. These groups are almost like one social block that is trend driven, with complex socio-economic signaling behaviours. Leveraging these behaviours can be more critical than focusing solely on product quality. This involves enabling Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) options to enhance affordability, creating rewards programs, and cultivating brand ambassadors who are recognized trendsetters.

HAN’S SUCCESS ACROSS CONSUMER GROUPS IN PAKISTAN AND BEYOND

Shan Foods is an example of a company that demonstrates a deep understanding of its consumer market, successfully building a brand that resonates across multiple income groups in Pakistan.

A producer and packager of spice and spice mixes in Pakistan, Shan has become an iconic brand in Pakistan and beyond, gaining traction in South and South-East Asia, the GCC, Europe and North America. Before Shan’s arrival, spices and spice mixes were a highly segmented consumer product with extremely fragmented distribution.

The key to Shan’s success lies in maintaining a focused selection of spice mixes they excel at, upholding strict quality standards, and ensuring affordability across all income groups. Additionally, Shan has built a brand that evokes nostalgia, reminding customers of home, loved ones, and special occasions. This deep connection with their customers has been the defining factor of the brand for over 30 years. The fact that the company never took a single dollar of debt is a testament to the organic distribution they have built through sheer perseverance and customer empathy.

Mobility platform Bykea, online payment app EasyPaisa, and fashion brand Khaadi are other examples of companies having achieved success across various income groups in Pakistan

CONCLUSIONS

Here are some key takeaways from our research that can help brands better understand and frame the consumer opportunity in Pakistan:

- The consumer market in Pakistan is complex, with consumer staples offering a large and deep market that enables platforms to reach the long-tail of consumers.

- While moderately segmented, the consumer market largely gravitates towards value-based purchasing.

- Scaling a true consumer business in Pakistan through online channels like paid ads is both limited and expensive.

- The best brands in Pakistan have built businesses by optimising conventional behaviours and practices across the population.

- Pakistan’s middle class, the youngest and fastest-growing segment, is crucial for any successful consumer business, both now and in the future.

- Although the online consumer market may be limited in the short term, it is poised to become one of the largest globally in a multi decade time frame, driven by demographics alone.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(1) Our hypothesis here has been proven correct with our investment in Deal Cart. Over a year, AOVs increased by 3-4 times across the platform as a result of laser-focus on building an online grocery led retailer that delivers the best prices to its customers. With better AOVs come better economics and a clear move into profitability; after all a 10% contribution margin on $10 is still less than 5% on $25.

By Saad Hasan

Stay informed anytime! Download the World Economic Journal app on the App Store and Google Play.

https://apps.apple.com/kg/app/world-economic-journal-mag/id6702013422

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.magzter.worldeconomicjournal