Unsplash/Jean Carlo Emer Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland.

In 1933, Hitler began putting the party’s core racist and nationalist ideology into practice, identifying who could claim Germany as home and who in their view, really belonged in the country.

This process went way beyond enacting legislation to define and exclude Jews from society: the Nazis launched misinformation and hate speech campaigns vilifying and dehumanizing Jews, and sanctioned acts of terror that destroyed people’s places of worship, livelihood, and homes.

As Germany gained territory in Europe under the guise of uniting German-speaking peoples, they ensured that similar systematic campaigns took place in the countries under their control.

US Holocaust Memorial Museum/Yad Vashem Jews from Subcarpathian Rus are subjected to a selection process on a ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland.

Nazis emboldened by ‘deafening silence’

In his message for the International Day, UN Secretary-General António Guterres notes that the Holocaust was the culmination of thousands of years of antisemitic hate, aided by the decision of so many to do nothing to stop the Nazis. “It was the deafening silence – both at home and abroad – that emboldened them”.

This, he continues, was despite Nazi Germany’s hate speech and disinformation campaigns, contempt for human rights and the rule of law, the glorification of violence and tales of racial supremacy, and disdain for democracy and diversity.

“In the face of growing economic discontent and political instability, escalating white supremacist terrorism, and surging hate and religious bigotry – we must be more outspoken than ever,” added the UN chief, drawing a parallel between the Holocaust and the present day.

UN News/ Conor Lennon Dolls made by stateless Jewish children living in UN displaced persons camp in Florence after the Second World War, on display at UN Headquarters

After the end of the world

The UN Outreach Programme on the Holocaust scheduled a series of events in January and February at UN Headquarters in New York, illustrating the “home and belonging” theme, including a ceremony to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day, on 27 January.

One of the exhibitions currently on display at the UN, and continuing until 23 February, centres on the experiences of the Jewish refugees who found themselves scattered across Europe, in dire need of help.

After the End of the World: Displaced Persons and Displaced Persons Camps, displays documents and photographs from the archives of the United Nations and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, and explains the role of the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), which was set up to resettle those displaced by the war and the Holocaust.

As well as information, and photographs of refugees, the exhibition contains several artifacts, including dolls made by stateless Jewish children who were living in a displacement camp in Florence, Italy, after the war.

Misinformation, stereotypes, and antisemitism

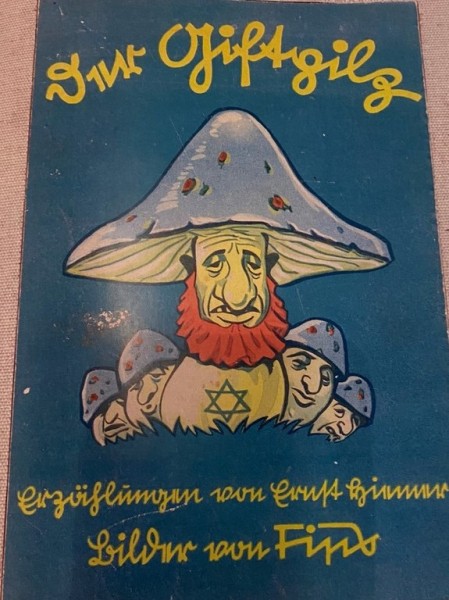

UN News/ Conor Lennon Copy of “Der Giftpilz” (The Poisonous Mushroom), an antisemitic children’s book, on display at UN Headquarters.

Displacement due to conflict and persecution remains a feature today, and misinformation and hate speech, which spread rapidly around the world thanks to the internet, continue to put lives at risk.

Located next to the exhibition on displacement, is another installation illustrating the stereotyping, misinformation, and conspiracy theories used by the Nazis, to vilify Jews, Roma, migrants, LGBTQIA+, or other groups.

The aim of “#FakeImages: Unmask the Dangers of Stereotypes” is to challenge the viewer to unmask the lies that continue to divide and polarize communities, and both exhibitions encourage visitors to draw comparisons with present-day antisemitism. “#FakeImages” is on show until 20 February.

The Book of Names

Until 17 February, visitors to the UN can also see the Yad Vashem Book of Names of Holocaust Victims, which details alphabetically the name of each of the approximately 4.8 million Holocaust victims that Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, has so far documented and confirmed.

Whenever possible, the book shows the date of birth, hometown, and place of death of each victim.

The names are taken from Pages of Testimony – forms created by Yad Vashem to record the brief life stories of Jews killed in the Holocaust – as well as from various lists compiled during and following the Holocaust, and subsequently reviewed by Yad Vashem experts.

Visiting the UN:

The exhibitions in the UN lobby are free and open to the public. Guests are welcome to visit the exhibitions during regular hours (Monday-Friday, 9 am – 5 pm). For more information check the United Nations Visitor Centre entry guidelines.

Soundcloud

Virtual events

UN Holocaust Memorial Ceremony

The event includes remarks by United Nations Secretary-General; the President of the 77th session of the General Assembly, the Permanent Representative of Israel and the Deputy Representative of the United States to the United Nations.

Professor Debórah Dwork delivers the keynote address. Jacques Grishaver of the Netherlands will share his testimony as a survivor of the Holocaust. Professor Ethel Brooks will speak to the persecution and mass murder of the Roma and Sinti. Two grandchildren of Holocaust survivors will also address the ceremony – Professor Karen Frostig and Michael Shaham. Musicians who will perform, include Shoshana Shattenkirk, Michael Shaham (who will perform on a Violin of Hope). Professor Renée Jolles performs a piece for violin specially composed by Victoria Bond for the 2023 Holocaust memorial ceremony. Cantor Nissim Saal, recites the memorial prayer.

The ceremony, which takes place on 27 January at 11:00 AM Eastern Time, is streamed live on the United Nations YouTube channel, and then available on demand.

Each life a world: Survivors share their stories

As part of a collaboration with the UN, the Jewish non-profit organization B’nai B’rith, continues its series of annual virtual events, featured on its YouTube channel, with testimony from Holocaust survivor, Ivan Lefkovits.

Professor Lefkovits, along with his mother and older brother, were deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944. His brother, who was 15, was murdered. Professor Lefkovits and his mother survived the war, and in 1969 established the Basel Institute for Immunology.