In 2011, during the January 25 Revolution, “bread” was one major rallying cry for the millions of protesters who took to Egypt’s streets demanding change. Bread signified decades of Egypt’s economic struggles, culminating in poverty that aff licted nearly a third of the population while youth unemployment was around 35%.

EXTERNAL WOES

The country’s challenges were severely exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the international supply chain disruptions that occurred in 2022, and a severe dollar shortage that same year with billions of dollars fleeing the economy. Finally, since October 2023, the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza has had a rippling effect on Egypt, whose economy relies significantly on dollar revenues from tourism and the Suez Canal. While the number of tourists declined in late 2023 before partially recovering in early 2024, the Suez Canal saw its traffic plummet by 66% from mid-December to early April as a result of Houthi attacks in the Red Sea.

On the debt front, the crisis worsened in 2022 when the US raised interest rates, causing a prolonged exit of investment, said Egyptian economic researcher Mohamed Gad in an exchange with WEJ.

The cost of servicing debt continued rising afterwards as domestic interest rates grew and the national currency began to weaken in 2022. By September 2023, the country faced a whopping $51 billion due within a year, an amount equal to roughly one and a half times its 2023 foreign currency reserves.

Thus, the country’s external debt reached a record $164.5 billion (around 92.7% of the GDP) in 2023, more than doubling since 2016. Egypt now boasts the highest debt-to-GDP ratios among emerging markets and middle-income economies, according to the IMF.

COSTLY NEW CAPITAL

Ambitious megaprojects, intended to create jobs, attract foreign investment and sustain economic growth, have ultimately led to increasing the country’s debt without delivering fully the expected results.

Among these endeavours is the ‘New Administrative Capital,’ a sprawling, futuristic city of highrises set to replace Cairo. But the scale of some of its undertakings—Africa’s tallest building, an artificial river, the Middle East’s largest church, and the country’s largest mosque—entailed considerable costs. The project has absorbed almost $60 billion in total so far. While Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi has repeatedly insisted that not a single pound from the government’s coffers was spent and that all the funding came from investors, Saheeh Misr, an independent fact-checking outlet, argues the project has aggravated the country’s economic crisis.

Today, almost nine years after the f irst announcement, more than 70% of construction for the first phase has been completed, even though the program suffered from the withdrawal of its original Emirati backers and the insufficient funding brought by Chinese investors. According to Khaled Abbas, chairman of the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD), the company responsible for developing the new urban centre, the new capital is now home to 1,200 families, a fraction of its projected population of five million.

MONETARY OR FISCAL ISSUE?

In March 2024, as interest payments consumed more than 45% of all revenue, the IMF agreed to finance another $5 billion to Egypt’s 2022 $3 billion loan contingent on structural reforms, spread over 46 months. To comply with the IMF’s conditions, Egypt allowed the pound to float and enacted a 6% interest rate hike, the largest in its history.

As a result, the pound plummeted by 40% within hours, reaching a record low, but the inflation rate declined.

The IMF’s recipes might be part of the problem rather than the solution, believe critical economists. “In Egypt’s case, the IMF’s insistence on devaluation as part of its prior actions led to inflation, which is countered with high interest rates, resulting in an economic recession,” said Salma Hussein. “This approach does not work for Egypt, as f iscal, not monetary, policies drive inflation. Raising interest rates doesn’t solve the problem, and the government needs to manage the budget more effectively.”

However, with its current regional role, Egypt might negotiate better loan repayment terms, notes Hussein. In February 2024, some relief came from a $35 billion investment deal with the Emirati sovereign fund ADQ to develop the Mediterranean Peninsula of Ras al-Hekma.

Additionally, to help ease the financial burden, the government intends to trade up to 10% of the ACUD on the Egyptian stock exchange by the end of 2024. The move is expected to provide between $3 billion and $4 billion. Gad and Hussein are hopeful that such a deal, combined with the partial return of investments to Egypt, could offer a reprieve that the Egyptian government could use to reassess its strategy.

HIGH SOCIAL COST

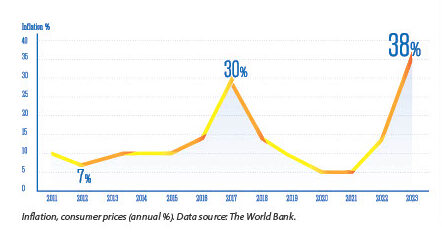

So far, the population has paid a high price for Egypt’s economic woes. In the past years, government spending on education and healthcare declined, eventually reaching 1.16% and 1.7% of Egypt’s GDP for fiscal year 2025/24, respectively. Prices for staple foods surged well beyond the headline inflation rate, which hit a record 38% in September 2023.

The crisis reverberated across Egypt’s social structure, forcing the majority of low- and middle-income citizens into debt. Ordinary Egyptians grapple with skyrocketing prices, inadequate healthcare, and power outages.

As noted by the IMF, the Egyptian government provided some relief to the most vulnerable through the Takaful and Karama programme, which was implemented for the first time in 2015 and has since expanded to more than f ive million households.

In early 2024, the government also enacted a $3 billion social protection package, which included an increase in the public sector minimum wage and targeted support for teachers and healthcare workers.

Egypt’s economy continues to struggle, but at least the country is at peace.

“All neighbouring countries are plagued by war, civil unrest, internal armed conflicts,” said Farah Mohamed, a customer service representative. “Life is hard, but at least we’re safe, and I hope one day we’ll make it out of this crisis.”

By Mohamed al-Afdal

Stay informed anytime! Download the World Economic Journal app on the App Store and Google Play.

https://apps.apple.com/kg/app/world-economic-journal-mag/id6702013422

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.magzter.worldeconomicjournal