Russia’s and China’s gas agreement has already been called “the top three-decade deal.” Its scale is quite impressive – in the next six years, the Chinese will be investing $55 billion in Russia’s mining and gas transportation system. But much more important than the numbers is the fact that the agreement formalizes that the two superpowers have common interests, at least for the foreseeable future. We are witnessing the emergence of new global political-economic blocs.

Of Key Interest

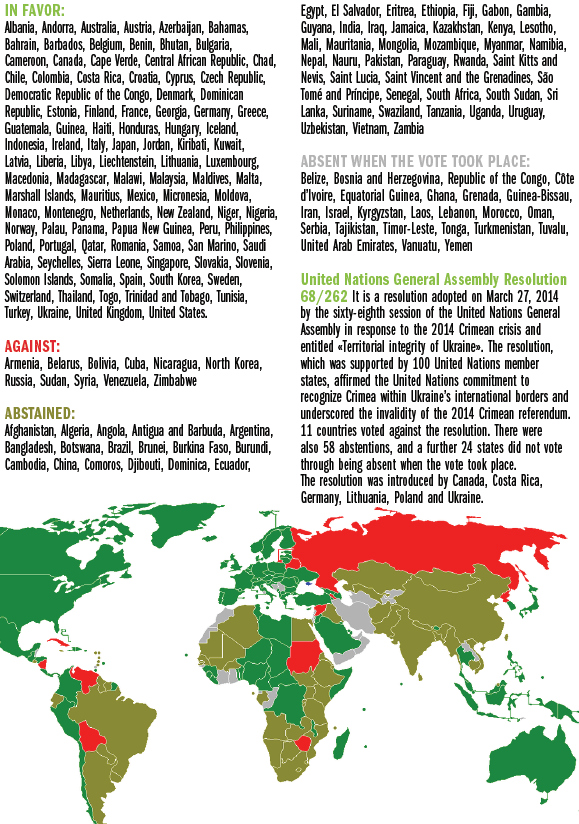

The UN General Assembly’s March 27 vote on Ukraine is a sufficient demonstration of the new alignment. The American draft resolution, which condemns Russia’s actions, was supported by 100 of the Assembly’s 193 members, after much preliminary work. The remaining countries refused to share the White House’s opinion in one way or another: States in open conflict with the U.S. voted against it, while those more experienced in diplomatic niceties abstained or simply left the room, which is considered to be a more polite form of disagreement. Among those that abstained were: all the BRICS countries, Kazakhstan, Argentina, Asian countries, and a large portion of South America and Africa. Those that did not participate in the vote included old geopolitical allies of the U.S., such as Israel. All of this suggests that there is a new system of blocs forming before our very eyes.

One could argue forever about the causes of the Ukrainian crisis, but the current U.S. administration’s strong desire to “punish Russia,” paired with the rather restrained attitude of the European countries toward the situation, is forcing a choice between two alternatives. Either the U.S. really remains the only country that can claim to be the supreme moral arbiter in all global conflicts, or there are economic interests behind the efforts of the United States and its closest partners.

In support of the second version is the dramatic increase in activity to promote two key trade agreements, which would give the U.S. preferential relations with two continents – Asia and Europe. In this issue of the magazine, we discuss the Trans-Pacific Partnership, while the Trans-Atlantic trade pact will be analyzed in the next issue. Before Crimea joined Russia, the European Union wasn’t inclined to sign the agreement, which wasn’t very favorable to Europe’s small and medium-sized businesses, but at the end of March, U.S. President Barack Obama visited key European capitals in order to prove that only by creating an “economic NATO” (as the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership has already been dubbed by experts) can the EU countries be protected from terrible Russia. Yes, the conditions offered to the Europeans aren’t that beneficial, but that’s the price to pay for “security,” the U.S. leader said – almost in so many words.

21st-Century Wars

Any superpower needs allies for war. But we’re not talking about war in the classical sense, with shooting and explosions; we’re talking about far more effective economic battles. The U.S. is undoubtedly ready to declare economic war today against its main geopolitical adversary, Russia, but it can’t succeed without the support of Europe. But Russian-European economic integration is already deep enough that ripping out the Russian part would leave a gaping hole in EU business, and the Old World doesn’t yet see compelling reasons for such a serious sacrifice.

And it should be said that business doesn’t just mean energy dependency, although Russia is undoubtedly the largest and most economical supplier of energy to the EU, and giving up such a supplier would most assuredly bring about catastrophic price changes for some European businesses. With the signing of the gas agreement with China, Russia has shown that it can quickly find new markets in Asia (you can read more about that as well in this issue of WEJ).

One of the major threats is considered to be Russia’s exclusion from the international payment system, which would create considerable difficulties for Russian companies doing international business. But this, too, shouldn’t be overrated. Jim Sinclair , one of the leading American stock-trading experts, believes that the BRICS countries can easily recreate a similar communications platform, like the current Swiss system.

And so, calculations with China may be done in the national currencies of the respective countries – yuan and rubles. And when the American payment systems MasterCard and Visa refused service to the cards of banks against which the U.S. had levied sanctions, it only spurred the creation of a Russian national payment system, perhaps in cooperation with the Chinese Union Pay or the Japanese JCB (more on this in the following pages).

One way or another, trying to squeeze Russia out of the international trade system is equivalent to firing a gun in the mountains – the avalanche won’t bury just one national economy.

A Guest at Normandy

Just as events to honor the anniversary of Allied forces landing in Normandy got underway, heads of the leading seven nations ostentatiously met, excluding Russian President Vladimir Putin from the gala dinner. With his characteristic irony, he wished them bon appétit, through journalists. But it’s no secret to anyone that the G8’s function in today’s world has practically disappeared: Making decisions for the global economy requires at least 20 of the largest economies, and at the G20 meeting last year, the question was raised multiple times of expanding the size of the group. The funniest part is that Putin didn’t feel isolated at all when he came to France for the celebrations; on the contrary, he was the most in-demand leader present, setting a record for the number of bilateral, high-level meetings.

By then, the results of the European Parliament elections were known, and were it not for the traditional restraint of the European press, the results would have been called downright shocking. In the UK, France, and several other countries, there were victories by opponents of the EU’s current course, as voters expressed their dissatisfaction with both the economy and the politics. Nigel Farage and Marine Le Pen, leaders of their respective winning parties, expressed their support for the Russian leader and criticized U.S. policy in Europe. While the heart of their programs includes populist statements on limiting migration, they also include very reasonable economic measures to protect their national markets. Of course, the Trans-Atlantic pact isn’t supported by these politicians (or the voters who voted for them).

Russia is unlikely to withdraw into itself, as its current and potential allies are interested in strengthening the partnership. At the end of May in Astana, Kazakhstan, an agreement was signed to establish the Eurasian Economic Union: For now there are three states: Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, but in the near future we can expect its expansion. In addition to the economic benefits, we shouldn’t discount the fact that for many countries today, Russia has become an alternative to Western domination. “The West is striking at Russia and thereby sending a signal to all the other countries. This isn’t just a conflict between the West and Russia; in some ways, it is a conflict between the West and China, the West and India, the West and South Africa, the West and Brazil, and so forth,” continues Karaganov. The situation in Europe is also not so clear, as we can see. Paradoxically, it is Russia that is now defending traditional European values. Its efforts to do so are unlikely to go unnoticed.

Text: Robert Abdullin, Chief Editor, World Economic Journal