It is believed that women in the 20th century won equal rights and opportunities. But does this mean that the market values them on an equal basis with men? Not at all. As proof of this, Bloomberg experts estimate that women make up only 8% of the CEOs of U.S. companies with the largest capitalization on the S&P 500. And the most striking thing is that the salaries of these women are 18% less than those of men in a similar position.

Inequality Prevails

Back in 1963, President John Kennedy signed into law the Equal Pay Act, requiring organizations to pay the same to men and women who perform the same jobs. Fifty years later, there is still no appreciable progress, and the issue of the gender pay gap in the U.S. is still acute. Last year, the average American woman earned 76.5 cents for every dollar earned by the average man – even less than in 2011, when the ratio was 77 cents to the “male dollar.” If the average annual income of men last year, according to the Census Bureau, was $49,398, then for women, the figure was only $37,791. Thus, over a 40-year career, the average woman working full-time would lose $443,369. And in order to earn as much as a man over her career, a woman would have to work almost 12 years longer.

Of course, this situation is reflected in pensions, which are directly dependent on wages. The formula is simple: The higher the pay, the larger the pension. It turns out that at the end of their careers, women still face inequalities. Because of their lower income in the United States, the average Social Security benefit for women above age 65 in 2011 was about $12,700 per year, compared with $16,700 for men of the same age. And the worst thing is that most women who are actively working today are likely to retire without having received all the benefits of equal pay. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), gender pay inequality will not disappear until at least 2058.

Younger women earn almost as much as do men of the same age and occupation, but the growth rate is much higher for men’s salaries, such that by middle age the difference becomes much more noticeable. “In the USA, the difference in pay is minimal between young men and women at the beginning of their careers. Over time, this gap increases; men are more often promoted and their wages increase more,” said Ariane Hegewisch, Study Director of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, in an interview with WEJ.

Actually, if we divide up the working population by age, it turns out that in 2012, women aged 15 to 24 earned 88 cents for every male dollar. For the age group 25-44, this figure dropped to 81 cents, and for women aged 45-64, it was only 74 cents. There is even greater inequality and discrimination when we consider race and ethnicity. Thus, the typical African-American woman gets only 64 cents on the dollar earned by her white male counterpart. It is even less for Hispanic women, only 55 cents.

In most countries, and the United States is no exception, the pay gap is most noticeable for people with higher education. “The biggest difference in pay by gender is in professions that work on a commission basis. For example, this applies to financial consultants,” explains Ms. Hegewisch.

A study conducted by the IWPR shows that income inequality by gender is inherent to virtually all common occupations, but the real estate sector is the worst. In 2011, female real estate agents earned an average of $728 per week, compared with $1,201 for male agents, or in other words, just 61 cents to the “male dollar.” The situation is not much better for financial managers: $991 compared to $1,504 for men, or 65.9%. A Bloomberg study shows that women can only earn equal wages with men in low-paying fields, especially those related to care for others (caregivers, nannies) – except here women earn more on average: $1.02 per male dollar. Obviously women who crave equality have to make a choice: to settle for low pay but be on a par with their male colleagues, or to earn significantly more, knowing that a male colleague with similar functions will be paid more.

It is indicative that the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index, released in September 2013, found that in equality of pay, the United States was ranked 67th out of 136 countries. Yemen is one notch higher (66th place) – a country which was recognized that year according to the rating as the most unfavorable country for women. The most equal income distribution among men and women was in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore.

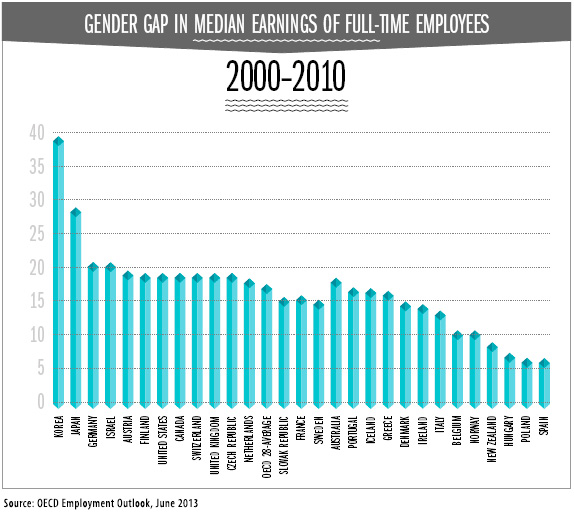

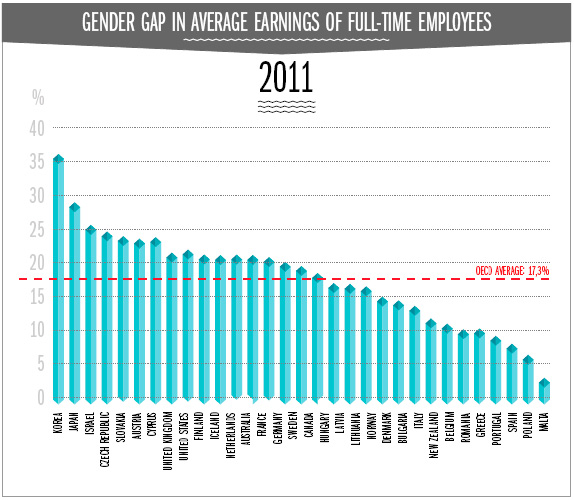

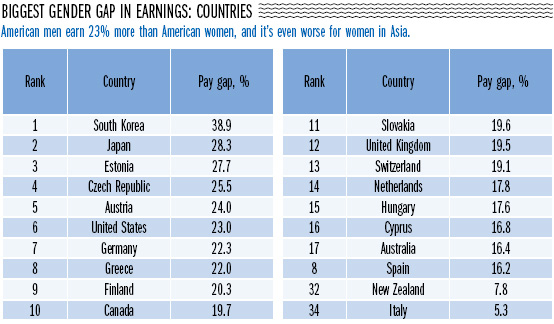

In Bloomberg’s rating of countries with the largest gender pay gap, the USA in 2013 ranked sixth (women’s wages were on average 23% lower than men with similar functions). There were even greater inequalities in women’s salaries in Austria (24%), the Czech Republic (25.5%), and Estonia (27.7%). But the Asian countries traditionally show the greatest inequality – especially Japan (28.3%) and South Korea (38.9%).

In the European Union, the gender pay gap tends to be much smaller on average than in the U.S., at 16%. Women in Slovenia, Poland, Italy, and Luxembourg, on average, earn only 10% less than men, whereas in the UK, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Germany, Austria, and Estonia, the gap is more than 20%.

In general, over the past decade certain social policies narrowed the gap, but in Portugal and Latvia, it has grown even wider. Yet women account for 60% of the graduates of European universities, and their progress is often better than that of men. However, if you look at the structure of the top companies and such professions as economics and politics, men still dominate. Thus among the largest publicly listed companies in the EU, only 15.8% of the members of boards of directors are women and only 3.3% of the chairmen.

“Although modern women have far more opportunities, it is still too soon to speak of full equality,” says Marijke Breuning, Professor of Political Science at the University of North Texas, Editor of American Political Science Review, summarizing these trends.

Who Is To Blame and What Is To Be Done?

There is no doubt that women today have more rights than, say, a century ago. They participate more actively in public life, in fighting for their rights, in pursuing a career. But although women today are so active and even surpass men quantitatively in American and European colleges and universities, employers still value them less highly than men. There are several reasons for this phenomenon. First of all, women on average work fewer hours; but this is due to objective circumstances – the need to care for children and other family members. Secondly, the women themselves place a lower value on their professional skills than do men. Thus a survey 66,000 undergraduates at 318 universities, conducted by Universum in 2013, showed that women on average expected a starting salary of $49,248 per year ($4,104 per month), while men’s expectations were already much higher. They expected an average salary of $56,947 (or $4,745 per month) at the early stages of their careers. Therefore, from the very beginning a person’s career, we get a difference in the starting positions of $7,699 per year.

“There is evidence that women are less likely to negotiate hard for a better salary than what is initially offered, so they often start out doing less well at their initial hire,” says Professor Breuning. “Depending on how salary increases are awarded, the problem may be compounded over time. This will be especially true if salary increases are calculated in percentage terms (3% of a smaller number will add less than 3% of a bigger number). I am not convinced that employers, generally speaking, are less willing to pay women a high salary. However, employers will not often voluntarily pay more than the employee is willing to accept.”

WEJ’s correspondent also discussed the reasons for the inequality in wages with other leading experts in this field. “The existing stereotypes play a major role in this situation: that the man is the breadwinner and that women’s pay is a secondary income source for the family. In addition, women are less likely to raise the issue of a pay increase themselves,” says feminism expert Patricia Glazebrook, Ph.D., a professor at the University of North Texas.

Indeed, the stereotype that still exists to this day, that “the man works, the woman takes care of the family,” has a strong impact on modern society, and in this respect Dr. Glazebrook agrees with Ms. Hegewisch, who told WEJ, “There are several reasons for the gender pay gap. Among them is the entrenched stereotype of ‘the male breadwinner,’ even though in today’s world, many women are raising children alone, and in a quarter of American couples it is the women who earn the larger portion of the family income. And the lack of transparency about wages often makes it difficult to know how much another employee in a similar position is earning. And if there is no transparency, then the employer has considerably more opportunities for discrimination – a bias that usually works against women. In other words, the greater the transparency, the less the pay gap. Transparency is ensured by involvement of trade unions in wage negotiations, and public access to information about rates, wages, and criteria for promotion. But, of course, not all inequalities are caused by discrimination. Nobody will dispute that unpaid housework is mostly done by women, which reduces their ability to excel on the job.”

Some experts have another view of the reasons for who is promoted and who is not. There is reason to believe that an employer making a decision on promotion is guided by women’s achievements, but by men’s potential – i.e,, expectation of future achievements. And as long as that is so, women have to make every effort not to lose their “place in the sun.”

Text: Olga Irisova